I’ve done two feature interviews with Alonzo Mourning — the first in 2009 and again in 2013.

Both times I found him to be driven, optimistic and so genuinely passionate about lifting kids out of poverty. His philanthropic work results in real examples of improved lives and communities.

And his return to the NBA after a kidney transplant is probably one of the most inspiring accomplishments in pro sports.

TRIBUNE PUBLISHING | July 2009

Alonzo Mourning’s Post-Game Show

By DEBORAH WILKER

If the expanding gulf between rich and poor could be summed up at a single street corner, few places could top the intersection of Biscayne Blvd and 14th St. in Miami.

To the east, the city appears ready for its close-up.

A sparkling new $482 million arts center sits majestically on both sides of Biscayne Boulevard, its pristine facade catching the last rays of sunlight off the bay.

But just steps away, the residents of Overtown live on some of this country’s bleakest streets, and are left to wonder once again why another massive public project was built around them – but so clearly out of their reach.

This is the stuff that makes Alonzo Mourning nuts.

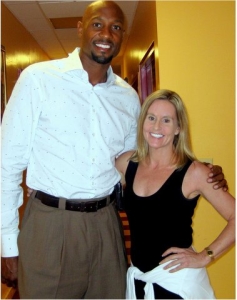

Alonzo Mourning with the local children who attend classes at his after-school community center — The Overtown Youth Center, in Miami

Though the recently retired NBA All-Star, Olympic gold medalist and member of The Miami Heat’s 2006 World Champion team, has survived life-threatening kidney disease, a 2003 transplant, and the unprecedented challenge of returning to pro form amid the assault of immune-suppressing drugs – it is not the notion of another kidney failure that keeps him up at night.

Rather it’s society’s inequities that haunt him he says – particularly when scenes of grinding poverty play out just inches from the good life.

This is why Mourning isn’t about to take the usual post-game route as he moves through this new stage of his life. While there were a handful of small TV and movie appearances years ago, show biz could not interest him less. He admits to missing the game, but there will be no broadcast career either; no in-depth analysis from one of the sport’s most well-spoken starting centers.

Rather, Mourning just wants to raise his family (two kids and one on the way) with wife Tracy, while also raising money for his Alonzo Mourning Charities, which supports a variety of community enrichment projects. He means it when he says he wants to make Miami “a better place to live,” even if it does sound like a Miss America platitude.

“Some people here made some bad decisions,” he says, pondering the millions squandered on the many stalled luxury condo projects bordering Overtown. “We do have some elected officials who are knowledgeable enough to know what really does need to be done for the community and for education – so why isn’t it done?”

Though Mourning sometimes sounds like a man whose next step is politics, he denies such aspirations.

“If I had a political seat there would be way too much red tape for me to deal with in order to do the things I want to do. This way I just do it. I don’t have my hands tied, and I don’t really have to answer to anybody. We just get it done.”

When Mourning talks about “this way” he is referring to The Overtown Youth Center just down 14th St., west of Biscayne – which he co-founded six years ago with local developer Martin J. Margulies. With space for just 200 local children in grades K-12, the waiting list is long.

The children who are accepted each year receive the kind of scholastic and social advantages that are taken for granted in other neighborhoods. Athletic leagues, dance classes, art, tutoring, computer labs, nutrition counseling, SAT prep, help with college applications, even college tours, health care and dental care if needed.

The children who are accepted each year receive the kind of scholastic and social advantages that are taken for granted in other neighborhoods. Athletic leagues, dance classes, art, tutoring, computer labs, nutrition counseling, SAT prep, help with college applications, even college tours, health care and dental care if needed.

“It cheers me to know that all that time going around asking for money, looking for funding, wasn’t for nothing,” he says. “I’m very confident that the efforts here are making an impact.”

One of the ways the OYC tries to ensure that, is by following the children after they age out – assuring them that someone has a continuing stake in their well-being.

And so, as the first group of students progress to various universities, safeguards are in place. The center’s teachers and guidance counselors will oversee students at least through their collegiate sophomore year, as well as when they return to the community for summer.

“These kids know when they come here that they have people around them who care about how they turn out,” Mourning says. “Kids are always looking for the approval of an adult. Watch Me! Look at this. See this Daddy, see this? All they want is assurance and attention.”

Scrunching his 6′ 10” frame into a tiny classroom chair , Mourning spent a recent afternoon talking about the relationship between rising crime rates, failing schools and a tough economy. He can’t imagine that anyone would disagree that a well educated population makes for a far better community than one in which more than half the kids drop out.

According to studies by the non-partisan Urban Institute headed by former Secretary of State Colin Powell, high school graduation rates in major cities have been hovering at about 50 percent. Nationwide the average is about 70 percent.

But in the poorest sections of some cities, among them Detroit, Indianapolis, Baltimore, Milwaukee, and Cleveland, studies say the gap is enormous: Just 35 percent of students graduate and Mourning says that from what he has seen Overtown, the rate is not even that good.

“Right in this neighborhood it’s only two or three out of 12 who graduate from high school. The statistics are really working against them. Eighty-five percent of the men and women who are incarcerated across the country have neither a GED or a high school diploma. So if we give these kids a chance to graduate from high school, we cut down on the chance of them becoming convicted felons.”

Mourning says he is just plain dumbfounded that Miami now has a firm plan in place for a new $515 million ballpark for The Florida Marlins, when “so much other stuff needs to be done.”

“You’ve got schools closing, and programs being discontinued and teachers being let go, yet you have stadiums being built? It’s just truly disappointing.”

The stadium – to be built on the old Orange Bowl site in Little Havana – will be both privately and publicly financed, the latter coming from a hotel bed tax levied upon tourists. Mourning is upset that this money was earmarked in such a way that it can only be used to enhance tourism and tourist related ventures — not for public education, or libraries.

“Who wrote that law – it’s ridiculous,” Mourning says. “I go back to what one of my coaches used to tell me: I guess common sense isn’t so common. Who allows this to happen? There are too many personal agendas going on here that have nothing to do with the good of the community.”

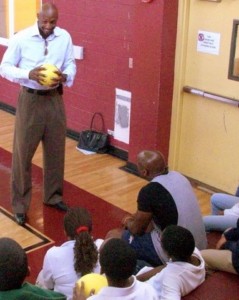

When the children learn Mourning is in the building, they’re inevitably excited, but at the same time subdued. No matter who stops by or who they encounter – a teacher, a celebrity , a parent, the President – the kids are taught that they must follow a strict protocol.

Smile. Make eye contact. Address people by name if you know it. Say “good afternoon.” Extend a hand.

“These are life skills,” Mourning says, as he gives a tour of the classrooms and shows off the big gymnasium. “These particular qualities are enforced here and the kids do understand the importance of them. Like learning to shake someone’s hand. It’s one of the things that is overlooked in a lot of these kids’ lives.”

Down the hall, a group of five-year-old girls rehearse a Broadway show-tune in the dance studio. They’re singing and dancing to one of the signature numbers from the musical “Annie” – “It’s A Hard Knock Life.” But Mourning is hoping they don’t find that out just yet.

“All of these children have the ability, they just don’t have the resources. What we can expose them to is key to their development. So taking them on field trips – just taking them outside this invisible fence up around this particular community – something as simple as taking them to the beach, it’s so important. The movies, arts events, every day things.”

And the not so every-day too.

Earlier this year Mourning packed up 50 kids and their parents and took them all by bus to President Obama’s inauguration in Washington D.C.

“That’s part of our protocol here, working with the entire family,” he says. “We enforce our relationship with the parents. If there’s something going on at home – something affecting them that prevents them from getting through the school doors in the morning, we know about it.”

Mourning acknowledges that he never “realized how difficult” all this would be. In his effort to raise the roughly $2 million a year it costs to keep the doors open, Mourning has lobbied everyone from House Speaker Nancy Pelosi, to athletes and entertainers, and just average families around town. He is also about to helm his 13th annual Summer Groove fundraiser, an around-town charity event encompassing concerts, ballgames, comedy shows, golf and a gala dinner.

“I was blessed to get a good education and to have had some really good people helping me out,” says Mourning, who earned a sociology degree from Georgetown University in 1992. “We’ve got to provide these kids coming up with the right angels too.”

Mourning has spoken openly about his own struggles as a teen in the Virginia foster care system, and more recently about his 2003 kidney transplant and winning battle to make transplant care more affordable.

He knows his life story was inspiring before kidney disease. Post-transplant he realizes he’s pretty much a sports anomaly – an example of will and courage that he hopes will resonate with the kids he’s trying to help.

He says that the anti-rejection drugs he had to take and still takes, were crushingly debilitating. How then was it possible to get back in such great shape, let alone pro-athlete playing shape?

“It was very challenging,” he said. “These drugs make you so weak and run down. It became even more of a challenge for me when I’d remember how my body used to respond. So I said to myself – OK – my body has muscle memory – my body remembers how it used to be because it was there before. So it became a matter of training my body to be how it was and I just wasn’t gonna give up on it.”

Up close Mourning appears to be as fit as ever, but he says his work-outs these days are not particularly exceptional. He practices yoga several times a week, takes spinning class, lifts weights and plays golf.

“Golf is great therapy.”

As he makes a last swing through the OYC classrooms, he stops to speak with a group of first- and second-graders who are learning about George Washington Carver. Mourning picks up one of the books, and starts to read aloud, ticking off Carver’s accomplishments in science, agriculture, teaching and race relations.

Then he stops. “He also invented rubber?” I didn’t know that. I learned something today!”

“So why was George Washington Carver successful?” Mourning asks the class.

Hopeful hands shoot up – but Mourning answers the question himself: “Because he had a good education.”